Can we all agree that the last year has been a wild one? And while all sorts of challenges remain everywhere, in our little corner of the world, there are encouraging signs of a modest return to pre-pandemic life. We’re vaccinated. We’ve hugged our children. The Seattle Mariners were briefly in first place—wait, what?

It’s also been a year since the publication of Tahoma and Its People and my first book talk via Zoom, for the National Parks Conservation Association. I’ve since created four separate presentations for groups to choose from, giving over 30 talks for about 2,000 people. Tahoma’s Biggest Stories is the flagship, focusing on the Native American presence at Mount Rainier going back over 9,000 years, and the far-reaching effects of climate change. A Virtual Field Trip in the Nisqually Watershed takes viewers from the Nisqually Glacier to the river’s runout into Puget Sound, visiting some groundbreaking restoration projects. Audubon Society chapters love Special Birds of Mount Rainier for its “quizzy” approach and detailed look at three endangered species. The newest talk, The Environmental History of the Carbon River, looks at our interactions with the river, the road, erosion, flooding, and mitigation efforts. Most of the talks are open to the public, and all are listed at https://jeffantonelis-lapp.com/appearances/. Contact me if you’d like to catch one, and I’ll send you the Zoom information.

I LOVE the Q and A session that follows each talk. It not only keeps me on my toes, but it gives me a chance to admit when I don’t know something or better yet, make something up (just kidding). In honor of a great first year for Tahoma, here’s a rundown of some of my favorite questions.

Question: Will Mount Rainier lose all of its glaciers?

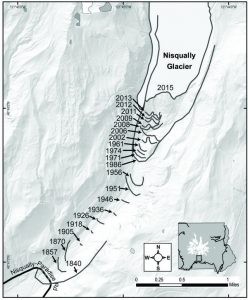

Answer: First, my standard disclaimer: I’m not a geologist, but I hang out with some! One of the most jarring comments I’ve heard from park geologists was Paul Kennard’s comment during one of his presentations that, “We’ve lost eight glaciers in my lifetime.” Wow! Of the two dozen remaining glaciers at Mount Rainier, all of which have retreated the furthest up the mountain’s slopes since record keeping began, we will probably continue to lose some of the smallest and lowest lying glaciers and perennial snowfields. Experts like Kennard and park geologist Scott Beason, however, believe that the massive size of some—especially their incredible thickness—will allow them to survive the current warming crisis. The Carbon Glacier, the thickest, at 700 feet at mid-glacier, and giants like the Emmons, Winthrop, Tahoma, Nisqually, and others, all of which originate at or near the mountain’s summit, will continue to dissipate but will most likely remain intact, at least in some form.

Question: My grandfather was a park ranger in California, and we inherited many of the Native American artifacts that he found over his career. Where do they belong?

Answer: I use another of my standard disclaimers on these types of questions: “I’m not an archaeologist.” In this case, I suggested that the family contact the federal agency from where the artifacts were removed and explain the situation. Agency staff should be able to advise of necessary action and whether the artifacts can be repatriated to tribes in the area.

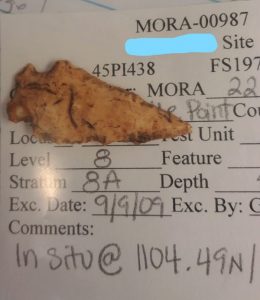

In the case of Mount Rainier, repatriation of artifacts is complicated because people from various tribal groups frequented many of the same sites. Not only that, some artifacts exceed 9,000 years in age, making it practically impossible to link most artifacts to contemporary tribal groups. These challenges led the park administration and local tribes to agree to house artifacts in the park Archives Department, but to allow access to tribal members and employees wishing to photograph, draw, or conduct research with the materials.

Question: Can we visit the archaeological sites at Mount Rainier?

Answer: In Tahoma, you may have noticed that I don’t disclose the exact location of archaeological sites. This is by design, the result of my training under retired park archaeologist Greg Burtchard. Greg loves to share his knowledge, but knows that ill-intentioned people could exploit specific locations for their own use. Could you imagine Mount Rainier stone tool artifacts for sale online?

While the answer is “No, we can’t visit specific locations,” you can visit some places to get a general sense of the Native American presence over the ages. One is the Ohanapecosh Campground, where excavations found multiple campsites, some at least 8,000 years old. This is an especially valuable site, because it marks the lowest elevation site in the park used by Native people. Most of their hunting and gathering activities occurred in the subalpine meadows, between 4,000 and 6,000 feet in elevation, where the resources they sought were most abundant. The Ohanapecosh sites represent stopover camp spots where people stayed when traveling between the high country and their low-lying villages.

Another spot to visit is west of Sunrise in the Frozen Lake area, where people hunted and butchered animals. Hike through here early in the day in mid-week when there are not many visitors present, and you can imagine the landscape a couple of thousand years ago.

Question: Will Mount Rainier be renamed?

Answer: I get this question at nearly every talk, and I love answering it. Captain George Vancouver, the British explorer who charted the region in 1792, upheld western European traditions by naming landforms and other geographic features in honor of others as a demonstration of fondness, gratitude, or respect. He named the imposing snow-covered monolith for Admiral Peter Rainier who, incidentally, never saw his namesake. Had Vancouver known that the people living around the mountain for generations had already named it, it wouldn’t have made any difference on his naming decision.

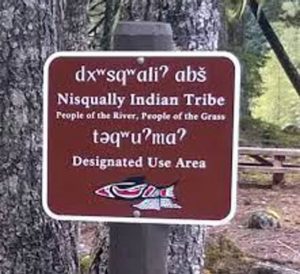

Anthropologist Allan Smith interviewed tribal elders in 1963 and reported that Puget Sound native people knew the mountain variously as Taqó·bid, Taqó·ma, Ta-co-bet, or Tacobet, as well as variations of Tahoma or Takhoma. Yakama people referred to it as Taxó·ma. There’s no universal agreement on a single meaning, but most linguists and Tribal experts trace it to something like “the source of all waters,” or “our mother who gives all.” Others believe it was a generic term for a snow-covered peak.

The battle to rename the “Great White Mountain” dates back over a hundred years, when the city of Tacoma campaigned for town and mountain to have the same moniker. Other efforts have failed to gain much traction, the last about a decade ago when a Puyallup Tribal member mounted a push for a name with indigenous roots.

But The Times They Are A-Changin’, and the conditions may be right for the long-deserved name change. The U.S. Department of the Interior oversees the National Park Service, and Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland made history this year as the first Native American to head the Interior Department and serve as a cabinet secretary. We may have the right person in the right place! And in terms of timing, the Puyallup Tribe just launched the latest bid to rename the mountain, with this recent coverage from KIRO 7 News: https://www.kiro7.com/news/local/changing-name-mount-rainier-new-effort-washington-tribes/RZ7STJVYDNFMLGPNCHZY62CRWI/. I aim to help in some small way—it will be exciting to see how things go, and I’ll keep you posted as things develop. In the meantime, keep your boots dry and your spirits high.

Breaking News—this just in: In last month’s blog, The Backstory on Those Notebooks, I detailed my nearly 40-year practice of writing field notes in Rite in the Rain notebooks. Well, the company recently began an Ambassador Program to recognize loyal users and as testers for new products, and they selected me as a Rite in the Rain Brand Ambassador! Free swag! A new logo on the website!

Breaking News—this just in: In last month’s blog, The Backstory on Those Notebooks, I detailed my nearly 40-year practice of writing field notes in Rite in the Rain notebooks. Well, the company recently began an Ambassador Program to recognize loyal users and as testers for new products, and they selected me as a Rite in the Rain Brand Ambassador! Free swag! A new logo on the website!

2 Responses

Ambassador Jeff!! Nice ring to it!

Thanks again Jeff for passing along your knowledge! We enjoyed the recent talk but couldn’t stay for the Q&A so it was great to see some of the questions posted here! Kent