If you’re anything like this G-O-D lover, (the Great Out Doors), the recent spate of sunny days and postcard views of “Ol’ Frosty” have set our sights on summer days in the backcountry. Right on cue, Mount Rainier National Park announced its new reservation system for backcountry camping and climbing, now administered by Recreation.gov. The park introduced its first Early Access Lottery to give visitors a chance to win an assigned date and time to book their trip online. If folks miss on the lottery, option two is to book a backcountry reservation online between April 27 and September 28. The park continues to hold about 30 percent of backcountry permits for walkups to a ranger station or Wilderness Information Center for hikes beginning on that or the following day. You can get the lowdown at https://www.nps.gov/mora/planyourvisit/wilderness-permit.htm.

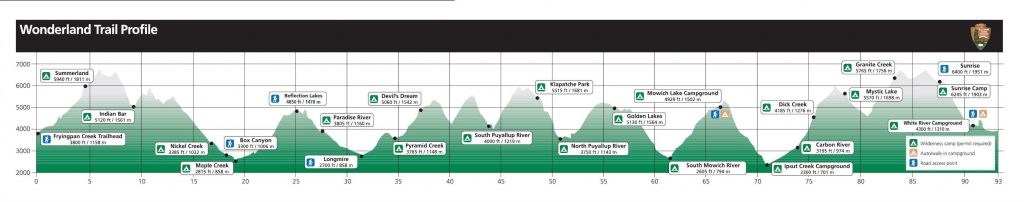

Of the 7,500 annual requests that the park receives for climbing and backpacking, about 2,700 are for the 93-mile Wonderland Trail. For the uninitiated, the trail that encircles Mount Rainier consistently makes the

“Ten Greatest, Most Awesome, Scenic, Challenging, Incredible Hikes in North America” lists in outdoor magazines and on websites. Most folks take a week or two to complete the trip, though it’s become a target of trail runners, those superhuman specimens composed of nothing more than ligament and lung. Runners broke the record for running the entire trail last summer—twice—each coming in at under 19 hours.

Before more than 12,000 backpackers and hundreds of thousands of day hikers began using the Wonderland Trail each year, it played a critical role in resource protection during the park’s early days. Built by rangers between 1907 and 1911, the trail enabled them to patrol the nascent national park to protect it from poachers, vandals, and fire. Congressional funding in 1915 helped complete a circuit that ran longer than today’s version. The Mountaineers, a Seattle and Tacoma-area based outdoor club formed in 1906, wasted no time in pressing their boot prints upon the newly forged footpath. In the irrepressible style of the day, packhorses carried provisions to feed the 90-plus hikers. The first group to circumambulate the mountain, they took three weeks to complete their trek.

In 1920, Superintendent Roger Toll penned this grand description: “There is a trail that encircles the mountain. It is a trail that leads through primeval forest, close to the mighty glaciers, past waterfalls and dashing torrents, up over ridges and down into canyons; it leads through a veritable wonderland of beauty and grandeur.”

A century later, Toll’s words ring as true as ever. Weather permitting, it repeatedly offers changing, breathtaking views as hikers tramp around the imposing monolith. Prominent features like Sunset Amphitheater, Gibraltar Rock, or the Willis Wall overwhelm us with their magnificence and remind us of our inconsequential smallness. As the 1915 Mountaineers trip reporter wrote that the mountain’s changing faces caused him to “gasp and gaze in silent awe and wonder,” we are dumbstruck by the constantly changing splendor.

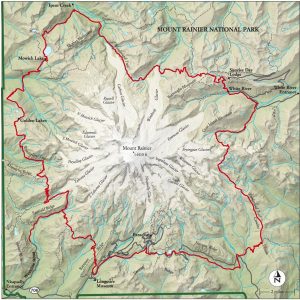

To celebrate the completion of my fieldwork for Tahoma and Its People a few years ago, I took a 6-day solo hike of the Wonderland Trail. Starting counterclockwise from Sunrise, a red-tailed hawk soaring in tight circles overhead seemed like a good omen.

In the early morning light of the second day, I struggled to find the route in the rocky moonscape between Seattle and Spray Parks. Later that afternoon at the North Mowich River, the washed out crossing presented a similar challenge. At each spot, I thanked the rock cairn builders for their tiny towers of river rock and volcanic ejecta. Although temporary, these markers guided me as I moved cautiously, often glimpsing only the next cairn up ahead.

At Golden Lakes at nightfall, a barred owl hooted its eternal questions: “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you-all?” Over the next few days, I watched other animals busily prepare for winter. A northwest deer mouse fed so intently at mid-trail that it was oblivious of me. A ground squirrel with its cheeks stuffed with seeds for storing, charged to within 10 feet before seeing me and darting for cover.

Rounding north and back toward Sunrise, a Clark’s nutcracker led the way up Cowlitz Divide. Scores of bird droppings marked the trail, stained blue from huckleberries. Camping at Olallie Creek, the Chinook Jargon word for berries, I picked two kinds of huckleberries for my morning gruel without even leaving my campsite. Set off the busy Wonderland Trail, it’s a camp so little used that even the gray jays have forgotten about it.

On my final morning, I returned to a spot that holds some important starting points. The undersized, protected camp in the Fryingpan Creek drainage sheltered small groups of hunters for over 1,500 years.

Even though other sites at Mount Rainier are much older, this one holds special significance. As the park’s first archaeological excavation, it’s the bedrock underlying much of our understanding of the presence of first people at Tahoma. The site holds great personal meaning, too. Sitting on the natural rock bench along the shelter’s back wall some years before, I began to feel the presence of the mountain’s forebears. I gained a new understanding of “the place and its people” that reaches back over 9,000 years, at last fully aware that I walked in the footsteps of the ancients.

As I prepared to hike out, I reflected on peoples’ relationship to the mountain, beginning with small groups that walked for days to hunt and gather on the mountain’s flanks over the ages. Up to contemporary times, when not long ago I watched climbers with headlamps on a moonless Milky Way night inch their way up Disappointment Cleaver on their way to the summit. All night they trudged upward, like religious pilgrims carrying votive candles to the high and holy sacred shrine.

I finished my notes and set off from the rock shelter. Before long, I spotted 12 mountain goats grazing on Goat Island Mountain. I’ve made more than a dozen trips up this valley over the last 40 years, but it was the first time I’d seen the mountain’s namesake on its hillsides. It was a fitting conclusion to a noteworthy hike.

I sometimes think of the Wonderland Trail as the Pacific Northwest’s largest three-dimensional, live-action board game. One player’s game piece might be a hiking boot; another’s a tent. Mine is a much-dented, beloved tin cup. Players move in either direction along the trail in short or long increments. Some are “destination hikers” intent on moving quickly through the landscape, a type one might call “Homo Directus.” Others, “journey hikers” who drink in every viewpoint and side trail and take two weeks or more to complete it comprise another breed, the “Meanderthals.” Like many hikers, I’m a mix of the two types. We move around the mountain, invisibly tethered to each other yet also separate, tested by terrain, weather, pack weights, and fitness levels. Even a trip shortened by foul weather, a bevy of blisters, or a wrenched knee leaves each hiker with a newfound link to the mountain and a grounding in the restorative power of living outdoors, even if for a short time. In this game, everyone wins.

For those serious about hiking the Wonderland either in segments or as a thru-hike, Tami Asars’ Hiking the Wonderland Trail is a great resource. I’ve picked up a few tips over the years too, that I’ll share sometime soon. In the meantime, keep your boots dry and your spirits high.

2 Responses

Great perspective on a gorgeous trail. I’ve never done the entire trail in one trip, but have had me boots on every section.

And thanks to you I learned a new Acronym today!

Happy Spring, Jeff

Meanderthals! Until I read this, I didn’t know I was one! Did know that I’m a Mosie Man though. I even have a license to mosey. My game piece? I suppose it’s my ‘fascinator,’ the Hasting’s Triplet magnifier I carry to stick my nose in wildflower business. Wonderful post Jeff!